(Heidegger, 1953)

Did Martin Heidegger anticipate by seven years

Thomas Szasz’s ‘The Myth of Mental Illness’ (1960)?

On the 79th anniversary of the violent death of

Anton Webern

Anthony Stadlen

conducts by Zoom

Inner Circle Seminar No. 292

Sunday 15 September 2024

10 a.m. to 5 p.m

|

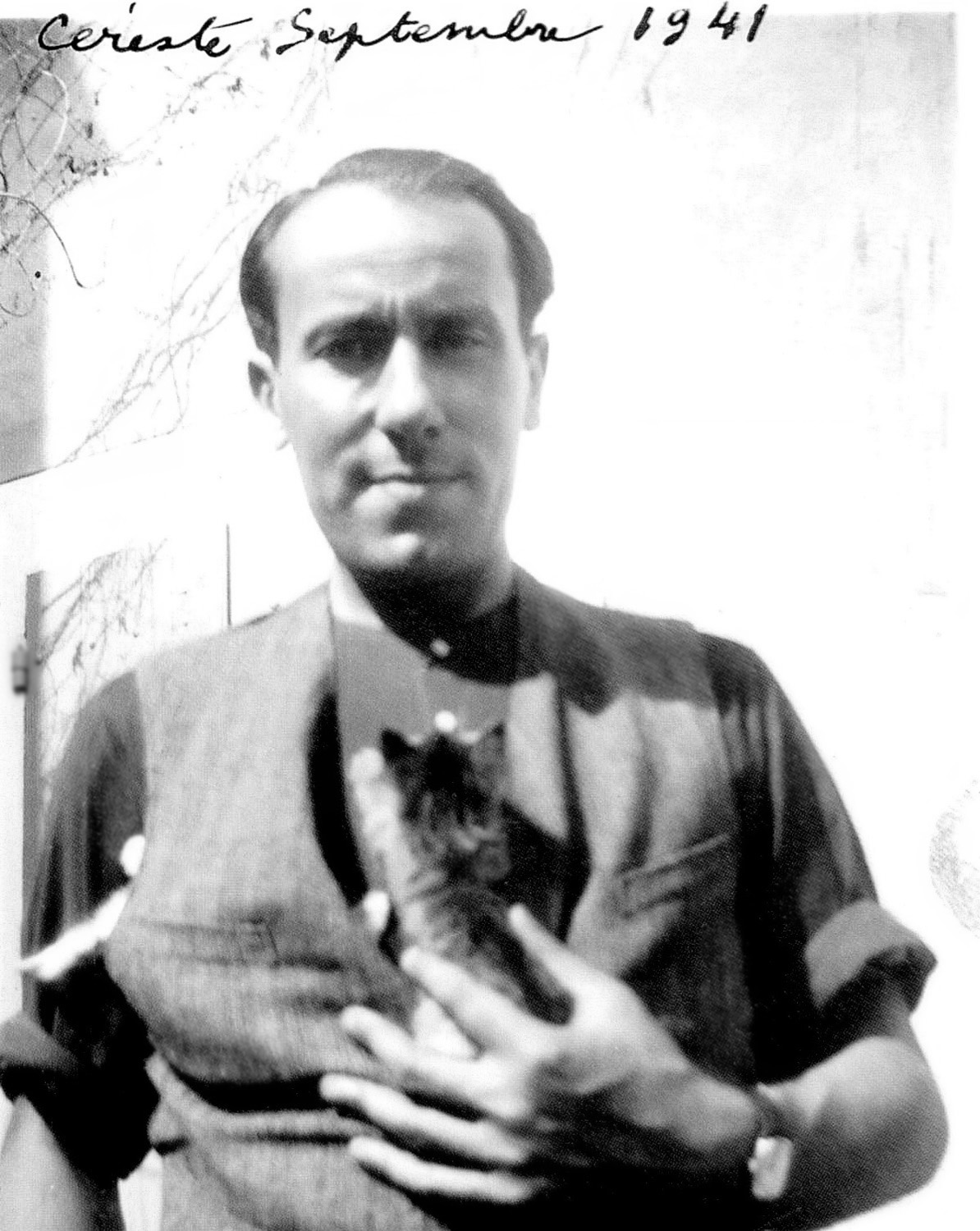

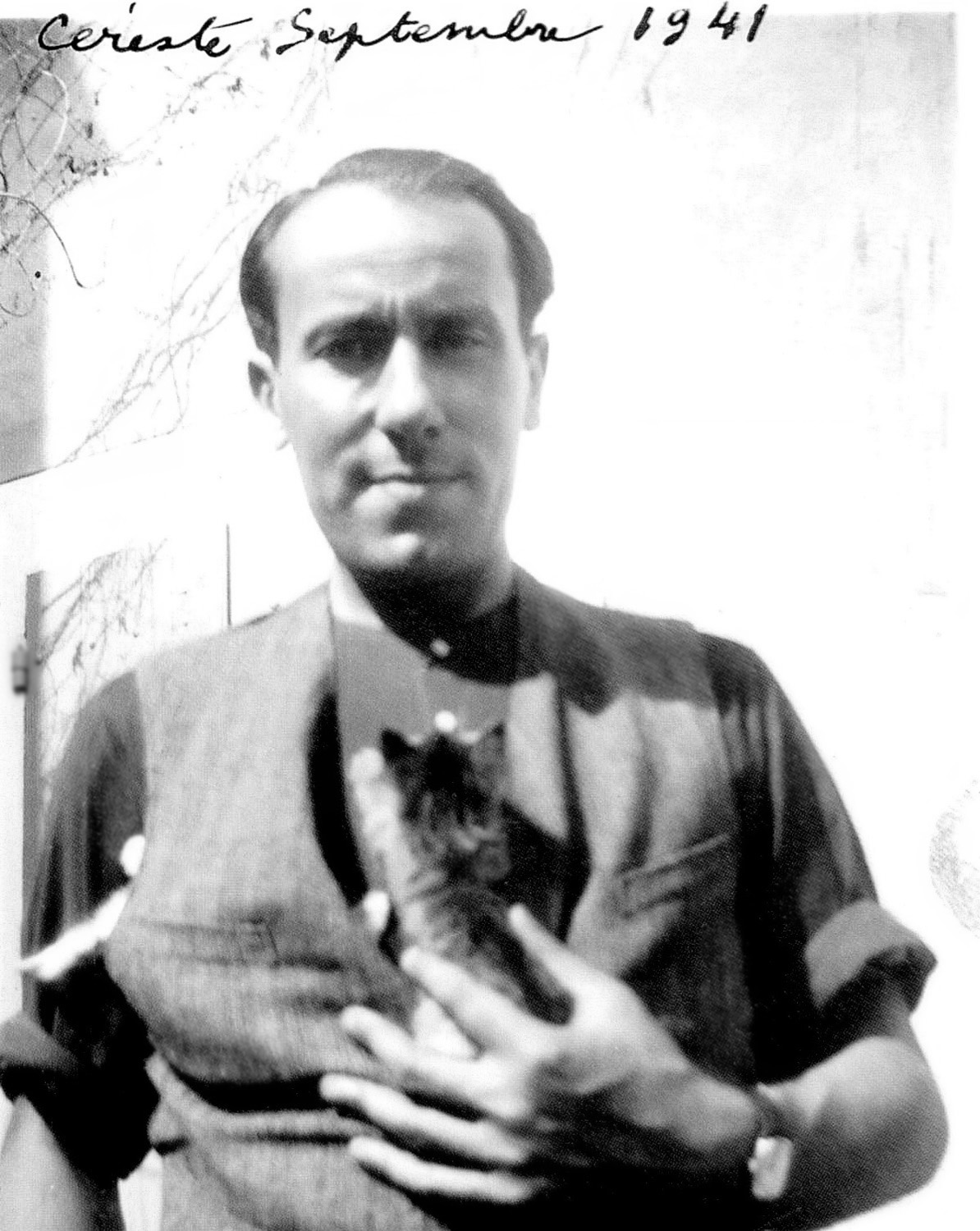

René Char

14 June 1907 – 19 February 1988 |

|

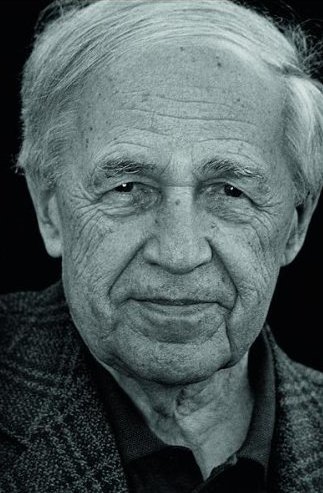

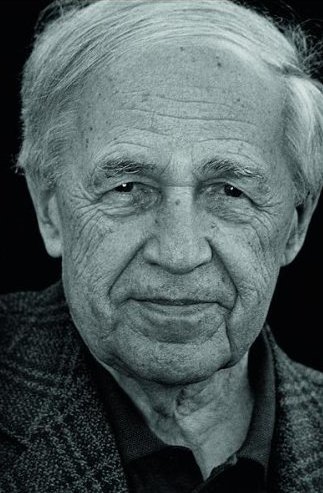

Thomas Szasz

15 April 1920 – 8 September 2012 |

|

Paul Celan

23 November 1920 – ca. 20 April 1970 |

|

Pierre Boulez

26 March 1925 – 5 January 2016 |

|

Sir Harrison Birtwistle

15 July 1934 – 18 April 2022 |

On 7 October 1950 the philosopher Martin Heidegger gave a lecture, ‘Die Sprache’ (‘Language’), in Bühlerhöhe (near Baden Baden). The lecture focussed on a single poem by Georg Trakl, ‘Ein Winterabend’ (‘A winter evening’).In 1953 Heidegger published an essay, ‘Georg Trakl: Eine Erörterung seines Gedichtes’ (‘Georg Trakl: An Elucidation of his Poetry’), in the journal Merkur (No. 61: pp. 226-258).

In 1959 Heidegger republished his 1950 lecture and 1953 essay as the first two chapters of his book Unterwegs zur Sprache (On the Way to Language), with the titles, respectively, ‘Die Sprache’ (‘Language’) and ‘Die Sprache im Gedicht: Eine Erörterung von Georg Trakls Gedicht’ (‘Language in Poetry: An Elucidation of Georg Trakl’s Poetry’).

Trakl in his poetry mentions ‘der Wahnsinnige’ (‘the madman’) many times.

Heidegger asks in his second chapter (1953: p. 237; 1959: p. 53):

‘[...] der Wahnsinnige. Meint dies einen Geisteskranken? Nein. Wahnsinn bedeutet nicht [...]’

(‘[...] the madman. Does this mean a mentally ill man? No. Madness does not mean [...]’)

The translator Peter D. Hertz, in On the Way to Language (1982 [1971]: p. 173), translates these words of Heidegger’s thus:

‘[...] the madman. Does the word mean someone who is mentally ill? Madness here does not mean [...]’

Readers could not divine from this translation that Heidegger had written:

(1) ‘Nein’ (‘No’) – he did not leave his own question unanswered;

(2) ‘dies’ (‘this’) – he did not write ‘das Wort’ (‘the word’);

(3) ‘Wahnsinn’ (‘Madness’) – he did not write ‘Wahnsinn hier’ (‘Madness here’).

The French translators of this book, Jean Beaufret and Wolfgang Brockmeier, in Acheminement vers la parole (1976: p. 56), translate this passage:

‘[...] Le Farsené. Le mot désigne-t-il un aliéné? Non. La démence n'ést pas [...]’

This is a little more faithful to Heidegger: an unequivocal ‘Non’ (‘No’); and ‘La démence’ (‘madness’), rather than merely ‘La démence ici’ (‘madness here’). But it also insists, without evidence, that Heidegger is discussing the ‘mot’ (‘word’) ‘madman’ or ‘madness’ rather than the madman himself or madness itself. Do these details matter? Yes, if one wants to know what Heidegger is doing here.

Is he making a very limited statement about a particular ‘madman’ in one of Trakl’s poems?

Or is he making a somewhat more general statement about ‘the figure of the madman’ in Trakl’s poems?

Or is he making a much more general statement: anticipating in 1953 the comprehensive proposition of Thomas Szasz, in his 1960 paper ‘The Myth of Mental Illness’ and his 1961 book The Myth of Mental Illness, that there is no ‘mental illness’?

This proposition of Szasz’s has the corollary that, in particular, if there be such a phenomenon as ‘madness’, then, whatever ‘madness’ is, it cannot be ‘mental illness’, nor can the ‘madman’, or anybody else, be ‘mentally ill’ – for the simple reason that ‘mental illness’ is a myth.

It seems unlikely that either Hertz in 1971 or Beaufret and Brockmeier in 1976 supposed that Heidegger in 1953 meant something quite so radical.

But might they have felt the need to play down even what he did seem to be saying, lest it make Heidegger himself seem a bit mad?

Parenthetically, we may note: that Heidegger himself may have thought of himself as Trakl’s ‘madman’ is suggested by Jacques Derrida in a lengthy passage which he calls a ‘parenthesis’ in his own Geschlecht III, the recently reconstituted and posthumously published (2018) third part of his sustained four-part meditation, Geschlecht, on Heidegger’s 1953 Trakl essay.

Derrida specifies as possible instances of Heidegger’s possible ‘madness’ his constant skipping between different and apparently unrelated instances of the same word in different poems. Certainly Heidegger has been criticised for this by other writers on Trakl, for instance Michael Hamburger.

Francis Michael Sharp, in his book The Poet’s Madness: A Reading of Georg Trakl (1981: p. 40), writes:

‘There is indeed madness in Trakl’s poetry, a madness which like all others, pursues its own lines of reasoning – which, in turn, the reader must pursue. It resists capture or exhaustion by the conceptual framework of psychiatry.’

What does Sharp mean by ‘madness in Trakl’s poetry’? Does he mean ‘madness’ depicted by the poetry, or ‘madness’ of the poetry itself?

Either way, ‘madness’ which truly ‘resists capture or exhaustion by the conceptual framework of psychiatry’ must, as Heidegger says, not be ‘mental illness’.

We have already devoted a number of seminars to showing that on a number of occasions it is to Heidegger’s great credit that he respects, as he does here, what the world calls ‘madness’ as what he calls an ‘other’ way of thinking, not reducible to psychiatrically conceived ‘mental illness’; but that then he tends to invalidate his own perception, by reaffirming aspects of psychiatric medicalisation and reification, often in collusion with his colleague the psychiatrist Medard Boss, for example in their otherwise in many ways radical Zollikon seminars.

We shall try to show in the present seminar that this double movement of a partial opening followed by a partial closing is also present in these two essays of Heidegger’s on Trakl. It is expressed among other ways through the metaphor of music.

Michael Hamburger and other writers have criticised what they see as Heidegger’s claiming spurious unity where there is manifest polysemy. This is a problem that pervades Heidegger’s work, and is in no way confined to his Trakl essays. But we shall draw attention to how this tendency of Heidegger’s takes a particular, musical, turn in his writing on Trakl. It is reflected in his ambiguity about ‘madness’, though neither ambiguity can be reduced to the other.

The quest for unity was there from the start of Heidegger’s lifelong journey. In 1947, when he had already been embarked on that journey for decades, Heidegger wrote in Aus der Erfahrung des Denkens (From the Experience of Thinking):

‘Auf einen Stern zu gehen, nur dieses’

(‘To go towards a star, only this’)

His ‘star’ had come into view in 1907, when he was eighteen. His Gymnasium rector Conrad Gröber, in Constance, had given him a copy of the philosopher Franz Brentano’s book On the Manifold Meaning of Being in Aristotle (1862). Heidegger’s single-minded, lifelong quest, his ‘star’, was the question: What is the one fundamental meaning of Being? He does not seem to have been deterred by the question that Ludwig Wittgenstein would later ask at the start of his Philosophical Investigations (1953): is there a single essential meaning of, rather than ‘family resemblances’ between, the manifold instances of, for example, the word ‘game’?

In a similar quest for unity, Heidegger points out that Trakl appears to emphasise (by spaced lettering) only one word, only once, in his entire poetical oeuvre: the word ‘Ein’ (‘one’) in ‘E i n Geschlecht’, where the meaning of ‘Geschlecht’ is highly ambiguous, as discussed by Derrida. The uniqueness of this emphasis by spacing of a word in Trakl’s poetry appears to be confirmed by the Konkordanz zu den Dichtungen Georg Trakls (Heinz Wetzel, 1971). Heidegger claims that this ‘E i n’ is, therefore, the ‘Grundton’ (‘keynote’) of Trakl’s entire oeuvre.

Heidegger appears to assume that, as Ian Alexander Moore puts it in his recent book Dialogue on the Threshold: Heidegger and Trakl (2022: pp. 82-3),

‘... to use Heidegger’s metaphor, poetic polyphony must resound from a tonic (Grundton). There can be dissonance, perhaps even modulation, but the music of poetry will always be rooted in a home key. Poetry, at least any poetry deserving of the name, is never atonal.’

But why? What justifies Heidegger’s assumption that there is a keynote, even of a single poem of Trakl’s, let alone of his poetry as a whole?

The Konkordanz (see above) shows that the word ‘Grundton’ (‘keynote’) appears nowhere in Trakl’s poetry, although ‘Ton’ (‘tone’) and its cognates appear many times. Of course, this does not prove that Trakl’s poetry has no ‘Grundton’, although any such alleged ‘Grundton’ could in any case only be a metaphor, as it must be in Heidegger’s usage.

Heidegger could have argued by pointing to a possible musical meaning of ‘Geschlecht’. Derrida gives as possible meanings: sex, race, family, generation, lineage, species, genre, genus. But neither he nor Heidegger mentions that ‘Tongeschlecht’ means musical mode, scale, or key. And neither ‘Tongeschlecht’ nor ‘Geschlecht’ with an explicitly musical meaning occurs anywhere in Trakl’s poetry, as the Konkordanz shows.

In the 1910s and early 1920s highly original but still tonal great music was still being composed, such as Béla Bartók’s string quartets, Leoš Janáček’s operas, Jean Sibelius’s later symphonies, Igor Stravinsky’s Les Noces, Ralph Vaughan Williams’s Pastoral Symphony, and Paul Hindemith’s song cycle Opus 23b (1922), a remarkable tonal setting of Trakl’s Die Junge Magd.

However, Trakl, who killed himself in 1914, was interested in Arnold Schoenberg’s early atonal music. And Schoenberg’s pupil and colleague Anton Webern set seven of Trakl’s poems atonally, in his Opus 13 No. 4 for soprano and orchestra (1922) and his Opus 14 for soprano and instrumental ensemble (1923-4). Webern wrote on 30 December 1929 to his friend the sculptor Josef Humplik that his Trakl songs were ‘just about the most difficult in this field’ to rehearse and perform. ‘Countless rehearsals would be necessary.’ (Webern, A., Briefe an Hildegard Jone und Josef Humplik, 1959: 12). Hindemith had arranged their first performance.

Anne C. Shreffler, in her book Webern and the Lyric Impulse: Songs and Fragments on Poems of Georg Trakl (1994), shows the crucial role these songs play in Webern’s development and oeuvre. Webern’s songs seem quite extraordinarily ‘in tune’ with Trakl’s poetry. Subsequent composers’ fine settings of Trakl, such as Heinz Holliger’s Siebengesang (1966-7) or Oliver Knussen’s Symphony No. 2 (1970-1), seem less paradigmatic.

As Shreffler writes (1994: p. 29):

‘By tearing apart the traditional connections between images, Trakl brought his poetry to a crisis point. By distorting traditional images and dissociating them from one another, Trakl produces something very much like atonality in music. He removed the unifying force of a single voice, an “ich”, resulting in a fragmentation of perspective.’

And (p. 33):

‘Much in the same fashion that Schoenberg loosened the traditional tonal connections between pitches, Trakl dislocated the structural functioning of classical poetic rhetoric.’

And (p. 244):

‘It is difficult to speak any more of “setting” a poem to music; this would be better described as “recreating” or “re-enacting” the text. Webern’s “re-enactment” of Trakl’s poetry enabled him to develop his atonal language to its highest levels of complexity and subtlety; the “difficulty” that results is essential to its expression.’

Heidegger does not appear to mention Webern (or Schoenberg) in his known writings. (He gets as far as approving Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms and Persephone.) However, no fewer than five of these seven poems set by Webern were discussed by Heidegger in his two essays on Trakl. Moreover, both the composer and the philosopher separated one particular Trakl poem, ‘Ein Winterabend’, from the others they selected. It is the only Trakl song in Webern’s Opus 13, of which it is the culmination, while Heidegger’s first chapter is also devoted to just this one ‘Wanderer’ poem (which Samuel Beckett, himself a Wanderer on a Winterreise, also admired). Heidegger’s second chapter, however, discusses, among many other Trakl poems, four of the six set by Webern in his Opus 14.

Even philosophers who discuss Heidegger’s writings on Trakl in depth do not appear to have discussed Webern’s or any other composer’s musical settings of Trakl, although Moore (ibid., 2022: p. 323, n. 53) mentions biblical allusions in ‘Ein Winterabend’ identified by Reinhard Gerlach in his analysis of Webern’s Opus 13 No. 4.

Both Webern and Heidegger respond sensitively to Trakl. In this sense there is an affinity between composer and philosopher, who also both revered Sophocles and Hölderlin, and shared the sense of the holiness of Being that Webern described in his letter to Alban Berg of 1 August 1919, leading (as if naturally) to his reporting that he had composed four Trakl songs:

‘[...] It is not the beautiful landscape, the beautiful flowers, in the usual romantic sense that move me. My object is the deep, bottomless, inexhaustible meaning of it all, and especially these manifestations of nature. I love all nature, but, most of all, that which is found in the mountains.

‘[...] Experimenting, observing in physical nature, is the highest metaphysic, theosophy to me. I got to know a plant called winter-green. A tiny plant, a little like a lily of the valley, homely, humble and hardly noticeable. But a scent like balsam! What a scent! For me it contains all tenderness, emotion, depth, purity.

‘I have written four songs to Trakl’s poems. [...]’

Die Reihe, No. 2 (1959 [1955]: p. 17)

But there is a fundamental difference between the responses by the composer and the thinker. Webern’s response to Trakl was atonal, Heidegger’s ‘tonal’. Although Heidegger repeatedly writes that Trakl ‘sings’, it is difficult not to regard Webern’s response as more authentic, more ‘in tune’ with Trakl’s own polysemy: his ‘atonality’.

It is highly improbable that Heidegger knew Webern’s songs when, three decades after Webern’s letter to Berg, he wrote his essays on Trakl. Heidegger’s colleague and translator François Fédier said (personal communication) that he had noticed, perhaps when attending Heidegger’s last seminar (in his Freiburg home from 6-8 September 1973, see:

https://anthonystadlen.blogspot.com/2023/01/285-heideggers-last-seminar-10.html),

that Heidegger had a boxed set of LPs of Webern’s complete published works. It can only have been the set conducted by Robert Craft in the 1950s, after Heidegger wrote his Trakl essays. (Pierre Boulez’s first complete Webern set was issued only after Heidegger’s death.) Heidegger told Fédier that someone had given it to him but that he had got little from it; and he presumably gave it away (as he did many books and records), as it was not among the LPs inherited from Heidegger by his son Hermann and, subsequently, by his granddaughter Gertrud (personal communications from the late François Fédier, the late Hermann Heidegger, and Gertrud Heidegger).

At the start of the 80th anniversary year of Webern’s fatal shooting by an American soldier in Mittersill on 15 September 1945 we shall try to honour his ecstatic musical response to Trakl.

Of course, there is no such thing as tonal or atonal poetry. And the relationship between the unity/polysemy polarity in poetry, music, psychotherapy in general, and Daseinsanalysis in particular is enigmatic. But these parallels are suggestive.

Our seminars have been explicitly devoted for nearly three decades to the search for truth in the foundations of psychotherapy. But they have also from the first been explicitly interdisciplinary. Todays seminar touches on Heidegger’s musical musings, but is not primarily about music. Nevertheless, in order to make sense of an ambiguity in Heidegger’s thinking, where he himself draws a musical analogy or metaphor, we shall take it seriously, and examine its implications.

We shall compare Webern’s composing with Heidegger’s thinking; and we shall suggest that Heidegger opened up a polysemous approach to Trakl’s polysemy only to close it off – just as in the Zollikon seminars he encouraged or at least tolerated Medard Boss’s developing a ‘Daseinsanalysis’ that remained medicalised and retained psychiatric diagnosis: in this and other ways making, in the words of the existential psychotherapist Martti Siirala, the ‘violent’ and ‘absolutist’ claim to ‘unmediated access to phenomena’. We shall ask whether Heidegger thus betrayed his own fundamental ‘No’ to his own question: ‘Is the madman mentally ill?’

This apparent fixation on and fetishising of the ‘one’, the presumed keynote, and tonality, is consistent with Heidegger’s avoidance, for half a century, of dialectics.

With the help of Francisco J. Gonzalez’s book Plato and Heidegger: A Question of Dialogue (2009), we have in other seminars and lectures explored, and shall in today’s seminar continue to explore, Heidegger’s decades-long disparagement of dialectics, from his earliest Freiburg lectures in 1919 to his last seminar in his home in 1973, and how this appears to limit his and his psychiatric colleague Medard Boss’s teaching in the Zollikon seminars and elsewhere, and their avoidance of the realm explored exactly at this time by their contemporaries Thomas Szasz, R. D. Laing, Aaron Esterson. Might this be remedied, as we have suggested, by developing, as Heidegger himself never did, his fleeting reference in a January 1920 lecture (reported by his student Oskar Becker, who was to become the philosopher of ‘mathematical existence’) to ‘diahermeneutics’?

Diahermeneutics in Daseinsanalysis, as we shall interpret it, does not mean some kind of chaotic disorder.

In his freely atonal works, such as the Trakl songs, Webern explicitly and with great courage renounced tonality and risked profound polysemy. It was, he said in his 1932 and 1933 lectures The Path to the New Music, ‘as if the lights had been put out’. But in these transitional works, and in his later twelve-tone, dodecaphonic works, he sought not anarchy but a higher unity, where notes are not hierarchically subordinated to a Grundton (keynote), but – as Schoenberg put it – relate ‘only to each other’.

Webern insisted at the start of his lectures that what Karl Kraus had recently said in Der Fackel about verbal language was true also of the language of music: that it was a question of ethics, not aesthetics.

So too, we seek – rather than a dogmatic domineering of Daseinsanalysand by Daseinsanalyst – two people devoted to a conjoint ethical, diahermeneutic quest for truth.

Of course, the interpretation by either a living composer or a living thinker of a dead poet’s poetry can serve only as a limited analogy to or model of the living psychotherapeutic or daseinsanalytic alliance. The poet cannot respond to the composer’s or thinker’s interpretation. The poetry cannot change in response to it.

Heidegger liked to speak of a ‘dialogue’ between Denker (thinker) and Dichter (poet); but his ‘dialogues’ with the dead poets Hölderlin and Trakl are necessarily monologues. He had the humility to say in 1945 when a friend played Schubert’s B-flat sonata: ‘This we can’t do with philosophy.’

Heidegger did have personal relationships with two other poets who were his contemporaries: René Char and Paul Celan. These relationships were very important both to him and to the poets. But Heidegger appears to have been ignorant of Pierre Boulez’s contemporary musical settings of Char, and could not have known of Harrison Birtwistle’s subsequent settings of Celan.

Heidegger’s happiest relationship with a contemporary poet was surely his late friendship with Char, whom he came to know when he visited Provence. Char, who had fought in the French resistance, defended Heidegger from the charge that he was still a Nazi, and they became good friends. However, Heidegger did not write about Char’s poetry in the way he wrote about Trakl’s, or respond to it as a thinker in detail as Boulez did as a composer in his Char trilogy, Le Visage nuptial, Le Solei des eaux, and Le Marteau sans maître.

On 25 July 1967 Celan was welcomed by Heidegger to his mountain hut in Todtnauberg. On 1 August Celan wrote a poem ‘Todtnauberg’, which alluded to the ‘star’ which Heidegger had been delighted to find carved on the well there, reminding him of the star of his lifelong quest. And the poem recalled Celan’s own

[...] line inscribed in that book about

a hope, today,

of a thinking man’s

coming (un-

tarryingly coming)

word

in the heart.

Celan, presumably disheartened, subsequently deleted the parenthesis, ‘(un-tarryingly coming)’.

At their last meeting, again in Freiburg, on 26 March 1970, Celan, who had been reciting his poetry, complained that Heidegger was ‘inattentive’, even though Heidegger had learned stretches of Celan’s poetry ‘by heart’. Heidegger – who in 1953 had replied with a decisive ‘No’ to his own question, ‘Is [Trakl’s] madman mentally ill?’ – perhaps did not let himself understand the sense in which Celan may have found him ‘inattentive’. Celan may have despaired of Heidegger’s truly attending to him by not merely repeating his words but perhaps speaking, perhaps about the Shoah, ‘a thinking man’s [...] word in the heart’, as Celan had written in Heidegger’s hut-book. Heidegger seems to have defended himself by deciding that Celan was not reasonable; not sane; not even mad in Trakl’s exalted sense which Heidegger had extolled seventeen years earlier – but a psychiatric case: ‘mentally ill’. He told a colleague: ‘Celan is sick – hopelessly.’

Celan drowned himself in the Seine twenty-five days later, on or about 20 April 1970.

The etymological meaning of the word ‘psychotherapy’ is attendance on the soul. Sigmund Freud called psychoanalysis ‘weltliche Seelsorge’, ‘secular care of the soul’, and in The Question of Lay Analysis insisted that psychoanalysis was not a branch of medicine. Boss, to the contrary, wrote to Heidegger: ‘As Erheller [Illuminator, Clarifier, Enlightener] of the spirit of technology you are also the founder of an effective preventive medicine.’ Boss gave his magnum opus the title Grundriss der Medizin, explicitly defining Daseinsanalysis as a branch of medicine, albeit a ‘holistic’ medicine.

This seminar is intended to clarify and strengthen what is good in Daseinsanalysis, while sharpening our awareness of dogmatic weaknesses and assumptions which may be transcended if we trace their origin in certain weaknesses and assumptions in Heidegger’s and Boss’s thinking as sketched above – particularly in their insistence on Daseinsanalysis as a medical practice.

This will be an online seminar, using Zoom.

Cost: Psychotherapy trainees £140, others £175; reductions for combinations of seminars; some bursaries; payable in advance; no refunds or transfers unless seminar cancelled

Apply to: Anthony Stadlen, ‘Oakleigh’, 2A Alexandra Avenue, London N22 7XE

Tel: +44 (0) 7809 433250

E-mail: stadlenanthony@gmail.com

The Inner Circle Seminars were founded by Anthony Stadlen in 1996 as an ethical, existential, phenomenological search for truth in psychotherapy. They have been kindly described by Thomas Szasz as ‘Institute for Advanced Studies in the Moral Foundations of Human Decency and Helpfulness’. But they are independent of all institutes, schools and universities.

No comments:

Post a Comment