|

Martin Heidegger

at the well by his hut above Todtnauberg |

|

| Emmy van Deurzen |

|

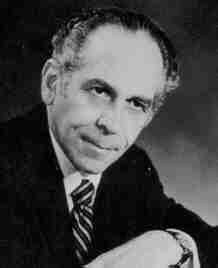

| Ludwig Binswanger |

In the 1940s, the psychiatrist Ludwig Binswanger described many idiosyncratic ‘worlds’ of his patients, such as ‘Ellen West’. The ‘swamp world’, the ‘tomb world’, and the ‘aetherial world’ seem to have been good phenomenological descriptions of Ellen’s actual experience. Binswanger also, only for a short time, tentatively proposed a relatively constant interrelated triad of ‘worlds’ supposedly of more general application, though explicitly, as he said, not meant to be exhaustive: ‘Umwelt’ (‘around-world’), ‘Mitwelt’ (‘with-world’), ‘Eigenwelt’ (‘own world’).

Half a century on, the existential therapist Emmy van Deurzen added a fourth: the ‘Überwelt’ (‘over-world’).

These four ‘worlds’, or ‘dimensions’, have been taught in training institutes, and regarded as an important part of existential therapy, at least in London, for more than thirty years. Trainee therapists say they have found them helpful. But how far do they clarify a client’s experience? May they not entail an arbitrary and restrictive conceptualisation? How is it that, for example, personal relationships are assigned in one book to the ‘Eigenwelt’ and in another book by the same author to the ‘Mitwelt’? How could such relationships be confined to one or other such partial ‘world’ or ‘dimension’, rather than by their very nature embodying an implicit shared search for wholeness that always already precedes and transcends such fragmentation into ‘worlds’?

As it happens, a hundred years ago, from 1919 to 1924, decades before Binswanger and van Deurzen proposed their three- and four-world schemes, Martin Heidegger had already, in five lecture courses (GA58,59,60,61,63) and in his essay The Concept of Time (GA64), proposed a triad like Binswanger’s, also with ‘Umwelt’ (‘around-world’) and ‘Mitwelt’ (‘with-world’), but with ‘Selbstwelt’ (‘self-world’) rather than ‘Eigenwelt’ (‘own world’).

But Heidegger, only a few years after introducing the ‘Selbstwelt’, denounced and renounced his own triad of ‘worlds’ as misconceived and thereafter appears never to have mentioned the ‘Selbstwelt’ again.

This was in 1925, even before he had published Being and Time (1927), and decades before first Binswanger and then van Deurzen proposed their sets of ‘worlds’. Neither of them could have been expected to mention in their initial proposals of ‘worlds’ either Heidegger’s earlier proposal or his subsequent retraction of his three-‘world’ scheme, as his relevant lectures were only published posthumously towards the end of the twentieth century. However, van Deurzen did not mention in her writings Heidegger’s proposal and subsequent retraction even after they had been published.

Today we shall explore Heidegger’s reasons for this early ‘turn’ in his thinking.

Heidegger, like Sigmund Freud, used such colloquial, rough-and-ready, terms as the ‘work-world’, the ‘classical world’, the ‘dream-world’, the ‘wish-world’. Freud, indeed, in his Gesammelte Werke (Collected Works) used ‘Mitwelt’ 9 times, ‘Umwelt’ 20 times, and ‘Unterwelt’ (‘underworld’) 14 times, but in their colloquial sense, without making them components of a formal scheme. Heidegger’s threefold world-scheme was meant to be more systematic.

However, in his 1925 summer term Marburg University lecture course, Prolegomena zur Geschichte des Zeitbegriffs (GA20, S.333) [History of the Concept of Time: Prolegomena (1992, p.242)], Heidegger denounced his own threefold system of ‘Umwelt’, ‘Mitwelt’, and ‘Selbstwelt’ as ‘grundfalsch’ (‘fundamentally false’).

He went on to write in Sein und Zeit (1927, S.118) [Being and Time (1962, p.155)]: ‘The world of Dasein is Mitwelt.’

So he retained ‘Mitwelt’, but not as a component of a triadic system. Our Mitwelt, as he now conceived it, is not merely one ‘world’, or one ‘dimension’, among others, of being human. Being-in-the-world-with-others is what being human is.

Furthermore, the early ‘existential’ and ‘phenomenological’ psychiatrists and psychologists, especially the self-styled ‘Wengen Circle’ (Ludwig Binswanger, Viktor Emil von Gebsattel, Eugène Minkowski, Erwin Straus), wrote about ‘the world of the compulsive’, ‘the world of the schizophrenic’, and so on: the ‘worlds’ of those whom psychiatrists traditionally classified as ‘degenerate’, not like ‘us’. Even those ‘existential’ therapists who today discard psychiatric diagnoses often claim that they are helping the client explore ‘the client’s world’. This may be helpful if it is a stage on the way to acknowledgement, by therapist and client, of what Heidegger called our ‘being-in-the-world’ [‘in-der-Welt-sein’]: the one world we all share. But this is often unclear.

It was already Josef Breuer’s and Freud’s revolutionary innovation in the last decade of the nineteenth century to regard their ‘hysterical’ patients, such as ‘Frau Cäcilie M.’, not as ‘degenerates’ who were living in their ‘own world’, as many, perhaps most, of their contemporaries supposed, but as sharing with the rest of us the one world in which we live and move and have our being.

In this respect, were not Freud and Heidegger more advanced than many existential therapists today?

Heidegger, as well as the Daseinsanalysts Medard Boss and Gion Condrau, argued explicitly against the supposition that ‘meaning’ and ‘spirituality’ are to be found in a separate, split-off, quasi-schizoid ‘world’. On the contrary, they insisted, our one, shared world is always already illumined by meaning and spirit.

It is in any case unclear why, if there were an ‘Überwelt’, there would not also be an ‘Unterwelt’ (‘underworld’), as documented from ancient mythology, through Virgil and Dante, to Freud and Jung. Should not such an ‘Unterwelt’ be a fifth ‘Welt’ in its own right?

And does Heidegger’s later vision of the ‘Geviert’ (‘Fourfold’) of ‘earth, sky, mortals and gods’, itself questionable, really justify a resuscitation of his long-abandoned three-‘worlds’ scheme and its augmentation with an ‘Überwelt’?

And again, why this fetishising by the later Heidegger of four? Why not, for instance, a sevenfold, traditionally implying greater wholeness? But Heideggerians and Daseinsanalysts reverently repeat the reference to the fourfold and do not question it.

We shall explore these enigmas today. We shall try in particular to clarify the logic by which Heidegger came to conceive, and then renounce, his own three-‘worlds’ theory.

Your contribution to the discussion will be warmly welcomed.

This will be an online seminar, using Zoom.

Cost: Psychotherapy trainees £140, others £175, some bursaries; payable in advance; no refunds or transfers unless seminar cancelled

Apply to: Anthony Stadlen, ‘Oakleigh’, 2A Alexandra Avenue, London N22 7XE

Tel: +44 (0) 7809 433250

E-mail: stadlenanthony@gmail.com

For further information on seminars, visit: http://anthonystadlen.blogspot.com/

The Inner Circle Seminars were founded by Anthony Stadlen in 1996 as an ethical, existential, phenomenological search for truth in psychotherapy. They have been kindly described by Thomas Szasz as ‘Institute for Advanced Studies in the Moral Foundations of Human Decency and Helpfulness’. But they are independent of all institutes, schools and universities.